By Doha Abdul-Raouf El Mol, Lebanese art critic and journalist

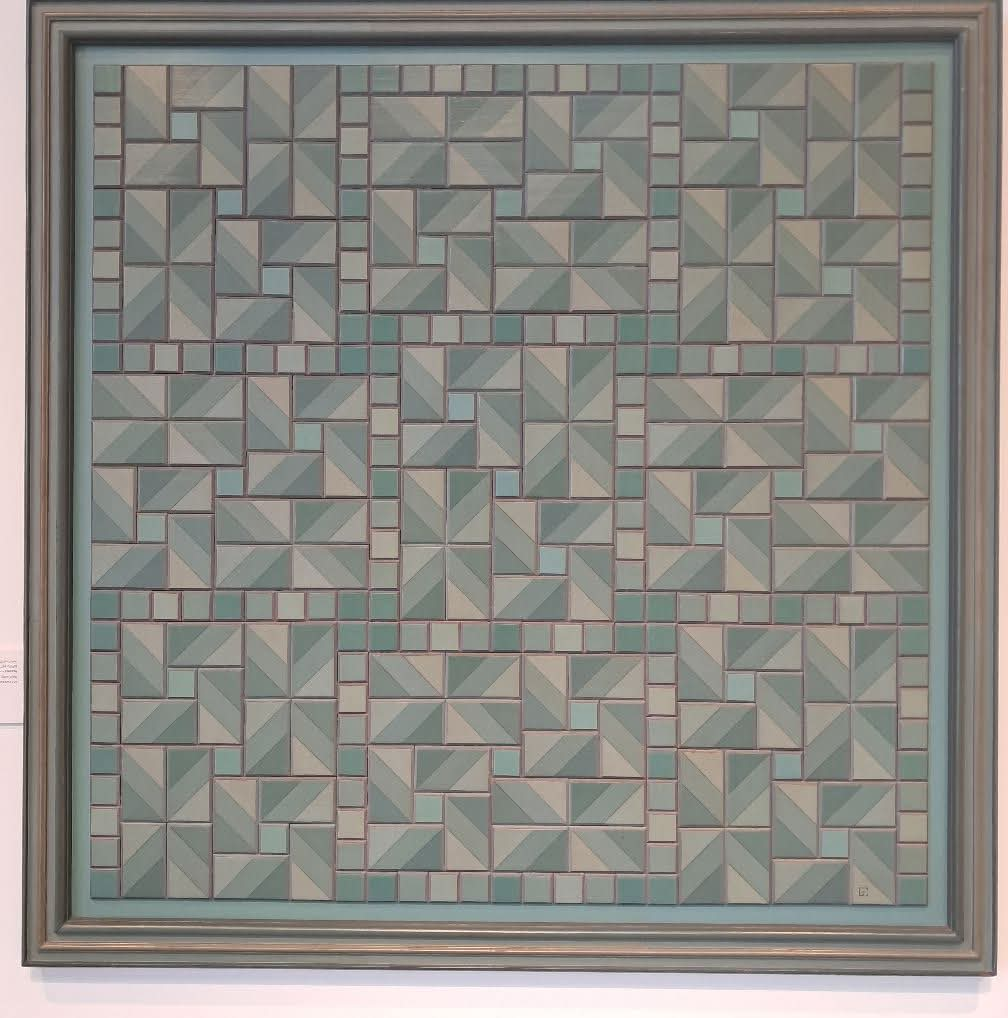

The painting of Lebanese artist Gebran Tarazi, displayed at the heart of Nabu Museum, poses a profound question about visual memory. His geometric canvas—composed of square and triangular rhythms and hues leaning toward aqua green —stands out as a pivotal work in the exhibition, for it embodies the passage from mythic symbolism to structural symbolism. The painting reconstructs ancient consciousness in a modern geometric language, transforming what was once mythological into a cognitive structure that bridges art, physics, and philosophy. Has the symbol, then, transformed over time—from Gilgamesh to geometry?

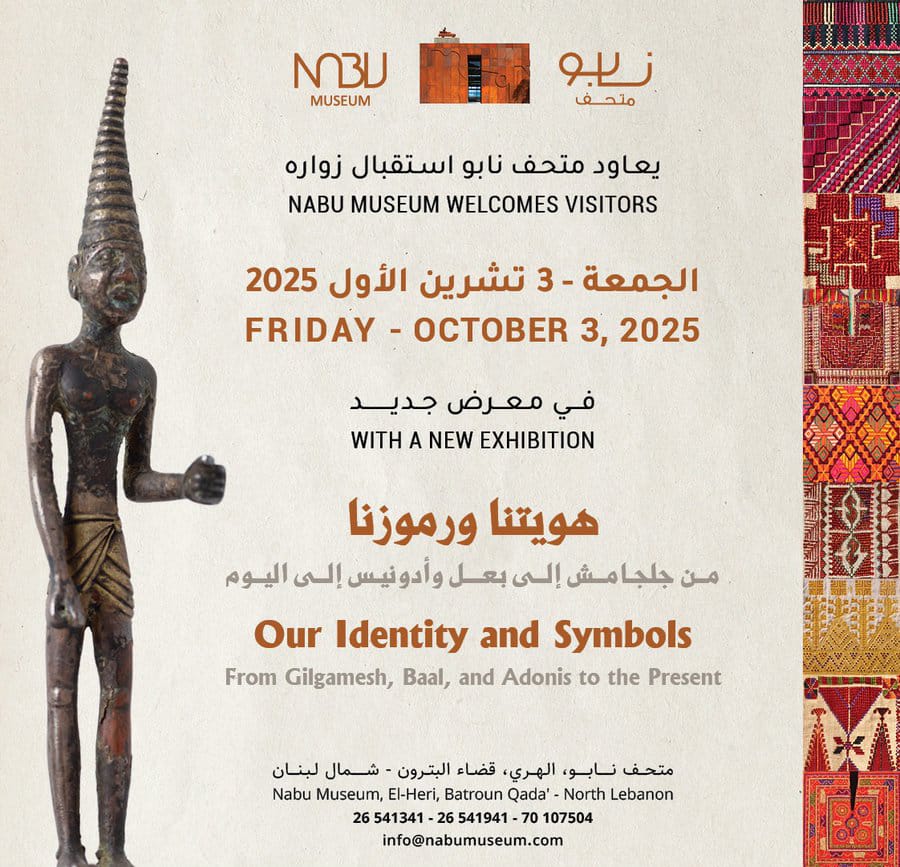

The exhibition, “Our Identity and Symbols: From Gilgamesh, Baal, and Adonis to the Present” inaugurated on October 3rd, 2025 and continues over three months is an intellectual and aesthetic project that traces how mythic symbols remain alive across millennia. It offers a journey through time—from the first myth to contemporary art, from weaving to painting, from belief to abstraction. It is not merely about the past, but about the continuity that forms the essence of our region’s cultural identity.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, myth was humanity’s language to confront mortality. In Baal’s myth, nature itself was a divine being that dies and is reborn. With Adonis, the cycle of life repeats eternally with the coming of spring. These are not mere tales but symbolic patterns describing the great movement between annihilation and rebirth, order and chaos. Tarazi’s painting does not depict these stories, but revives their inner logic, where geometric repetition parallels the cosmic recurrence of Adonis’ death and return. The closed square symbolizes the material body; the open triangle, the spiritual energy or ascension. The broken symmetry reflects the struggle between order and chaos, between life and death.

In this sense, myth transforms from narrative to visual system, from story to symbolic mathematics. What was once expressed through deity and ritual is now conveyed through color, proportion, and balance. But what about the formal memory that links weaving to painting in this exhibition?

The visual identity of our region has not been preserved in books alone, but in textiles, ornamentation, and embroidery. When you observe the embroidery of a woman from Jabal Amel or Nablus, you find triangular shapes, lozenges, and tilted crosses—not accidental motifs, but symbolic continuities reaching back to pre-writing cultures. The exhibition “Our Identity and Symbols” reminds us that embroidery is not merely a craft, but a living mythological archive. The symbols that once represented fertility, protection, or time became decorative motifs, and today have evolved into an abstract language.

Thus, Tarazi’s painting embodies this formal memory—its aqua-turquoise tones recalling the color of turquoise, once used in ancient rituals as a symbol of life. The regular repetition of squares evokes woven fabric, while the fine gaps between lines resemble embroidery threads. The painting thus builds a bridge between the folk hand that stitched the symbol and the contemplative eye that reinterpreted it. Is this painting, then, a cosmic equation? Does every system contain within itself a subtle deviation that produces motion? Does every symmetry require a hidden flaw to be complete?

The repetition of squares in Tarazi’s work—and even in the idea of weaving—does not create rigidity but a pulsing rhythm, as if every geometric cell throbs with quiet inner energy. This energy, discovered by Tarazi, is the visual equivalent of continuous creation, the mythic idea that the world is not made once, but renewed in every cycle, in every small variation within greater symmetry. So is all this not mere decoration? Rather, it is the physics of symbol: Tarazi’s painting shows how order can be alive, form can breathe, and repetition can remind us of eternity, not monotony.

The painting surpasses the traditional notion of the “beautiful,” which relies on representation or immediate emotion, to present a structural, rational beauty—the kind discussed by Kant and Malraux—born of perceiving inner harmony, not imitation. The painting becomes visual thought; it is not merely something to be seen but a way of thinking through the eye. Each line is an idea, each angle an equation. This is the profound transformation the exhibition proposes: that symbols once used in temples and rituals now find their place in galleries as systems of thought about existence. Can we say, then, that artistic structure is itself a mythic structure, or perhaps akin to the universal weave present in everything around us?

According to structuralist thought (Claude Lévi-Strauss), myth is not a collection of stories but a system of binary relationships—life/death, nature/culture, order/chaos. The painting, through its mathematical logic, reconstructs this same system: symmetries represent order, while subtle differences embody creative chaos.

It is a new myth in the language of forms. Whereas ancient myth used gods to explain the cosmos, the painting uses mathematical relationships to represent it. This is one of the exhibition’s key aims—to reveal that structure is the modern extension of myth, and that the symbol never dies; it only manifests through new tools. Has art in our region ever truly been separate from collective memory?

From the first Sumerian carvings to Byzantine mosaics, from Palestinian embroidery to modern abstraction, one symbolic thread evolves through time. Tarazi’s painting in this exhibition represents an abstraction of that memory—a reprogramming of ancient symbols into a contemporary geometric language. It is not an isolated work but a continuation of a civilizational line that sees form as a vessel for meaning. Every triangle can be read as a mountain, a spear, a movement, or the Tree of Life; every square as a box preserving a secret—an archaeology of symbols, not just a surface of color.

Thus, the exhibition’s title, “Our Identity and Our Symbols,” opens the greater question: Is identity built from memory or from renewal? Does this painting answer through form, or through both form and idea? Is identity here a movement between the fixed and the mutable, between inherited form and modern shift?

Just as the symbols of Gilgamesh, Baal, and Adonis recur—reinterpreted through embroidery, sculpture, and art—Tarazi’s painting redefines identity through visual order. It tells us that identity is not a slogan, but a network of relations and symbols that shape our way of seeing and thinking—and therein lies its modernity and aesthetic truth. Color, in this painting, is not secondary but a metaphysical language. The aqua-green hue evokes the spring of life, the fertility and rebirth of Adonis, and Baal, lord of rain. Yet it is also an intellectual color, calm and balanced, suggesting scientific inquiry—as though the artist sought to unite mythic intuition with analytic reason. Each tonal shade is like a note in a quiet melody: a watery geometry of memory. Through it, we perceive how meaning can live in color as it lives in words, and how a painting can become a small temple of harmony in a chaotic world.

If mythology studies the structure of ancient tales, this exhibition presents what might be called the science of visual mythology—the study of how old symbols transform into modern visual forms. Tarazi’s brilliant painting—without exaggeration—is a model of this process: a myth without gods, death, or resurrection, yet containing within its geometric relations the same cosmic meaning. Here, art is not a recollection of the past but a reactivation of the symbol in a new space. It is a philosophical act, reminding us that the symbol is the only language understood equally by past and future, for it belongs to structure, not to event. So, perhaps myth does not die—it only changes its material.

In the light of “Our Identity and Symbols,” we may say that this painting represents the final stage in the evolution of the symbol in our culture—from mythic carving to folk weaving, from ornamentation to abstraction, from form to idea. It embodies the notion that human beings, no matter how their tools change, still seek meaning through form, and immortality through order. What Gilgamesh did through his quest for eternal life, the painting does today through its question of the structure of beauty and knowledge.

It does not explain the myth—it lives it in a new language. As we look at it, we see the world’s memory re-engineered: each line a thread of myth’s fabric, each color a shadow of ancient consciousness, each square a living cell of identity still pulsing within us.

In conclusion, Tarazi’s painting is not merely an aesthetic piece in an exhibition—it is a visual manifesto of human consciousness in this region. It tells us that the symbols that forged our myths still work within us, no longer needing temples or gods but precise geometry and silent color to restore our capacity for contemplation. This is the essence of Gebran Tarazi’s painting in the “Our Identity and Symbols” exhibition at Nabu Museum in Northern Lebanon: to show that art is not just the memory of myth, but its intellectual continuation, and that identity is not fixed in history, but moves with it like an eternal geometric rhythm.

Thus, the painting becomes more than an abstract surface hanging on a wall—it becomes a map of the ancient soul, redrawn through modern intellect: a union between Gilgamesh, seeker of immortality, and the contemporary artist, seeker of meaning in form, both achieving immortality and life within this painting—whose cells renew themselves each time we gaze upon it.

English

English Español

Español Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français العربية

العربية